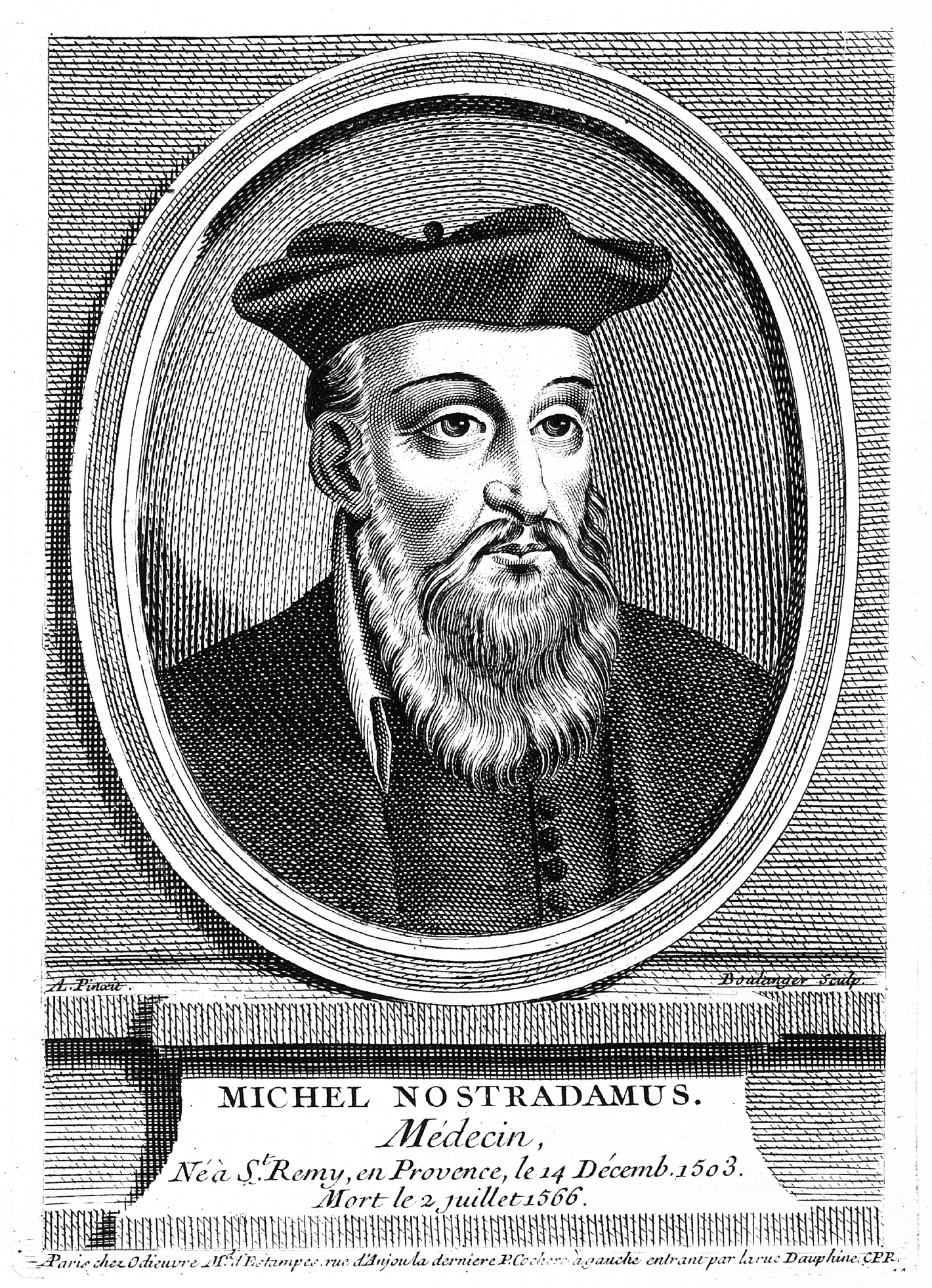

Candied fruits are the ancestors of modern sweets. They have been known since antiquity, but only really became popular in Europe thanks to Medieval Italians. Famous Nostradamus was a fan, with the richest people seeing them as an exquisite treat. Today, candied fruits are widely liked and accessible; however, few know that their recipes date back over a millennium.

Candying is a process where fruits are preserved by soaking them in sugar. The fruits are boiled in sugar syrup of increasing concentrations, allowing the sugar to penetrate into their cells, replacing the water. As a natural preservative, it prevents the growth of microorganisms. Candying takes place at fairly low temperatures, and contrary to other fruit processing methods most of the vitamins, minerals and other microelements are maintained. Flower petals, nuts and other products may be candied as well.

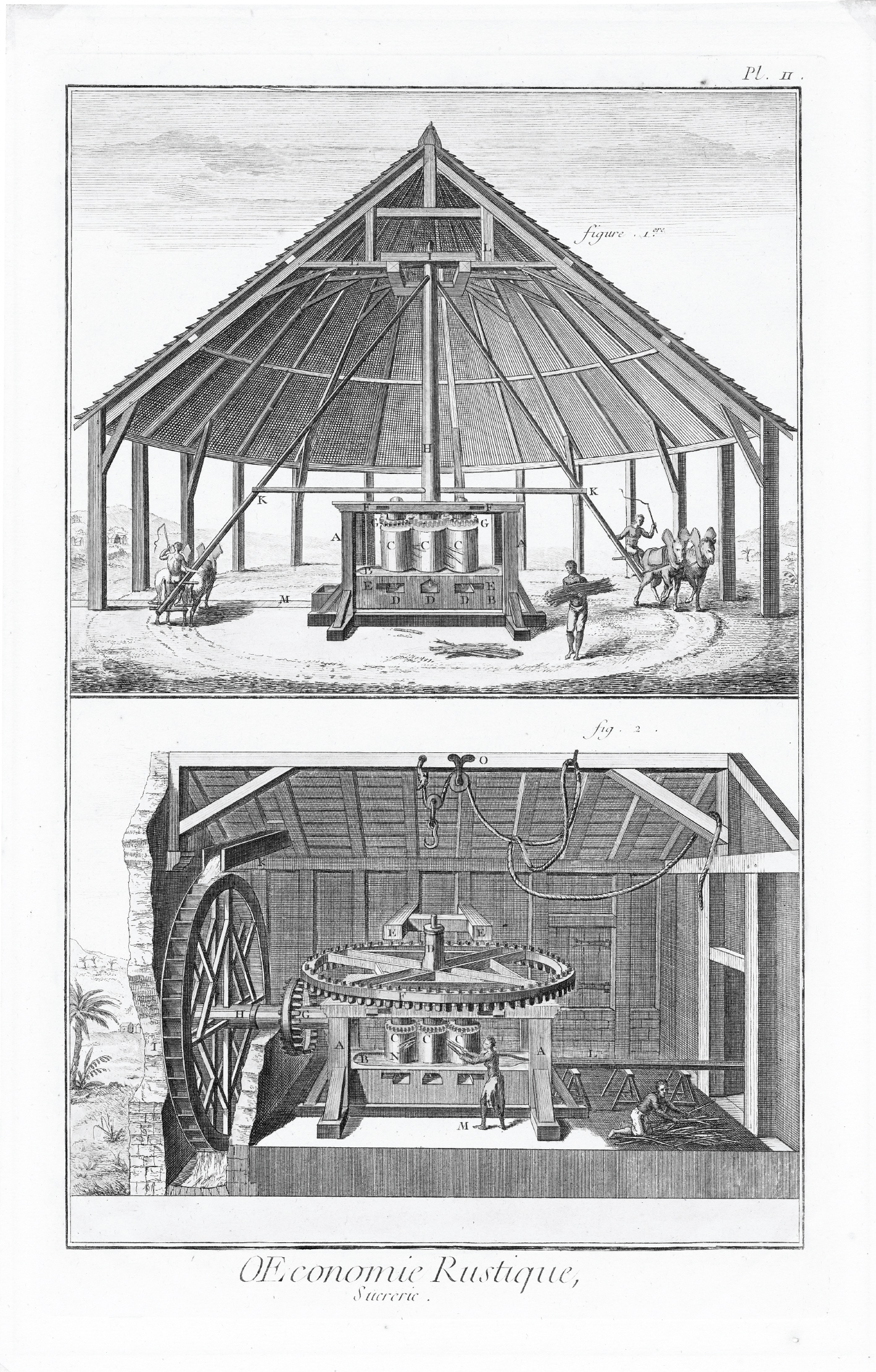

Back in those days, the processing took place in special, heated tubs. This would take two weeks, during which it was important to constantly monitor the temperature and concentration of the sugar syrup. Since sugar was very expensive, candied fruits were considered a luxurious treat that could only be afforded by royalty and the richest of aristocrats.

The verb to candy came into English from the East, via Italian candire and French candir. These probably appeared in the 13th century, and originated from the Arabic word quandi, meaning “made of sugar”. This word, in turn, probably comes from the Arabic name for the island of Crete: Candia, which they controlled for a long time, establishing sugar cane plantations and refining sugar.

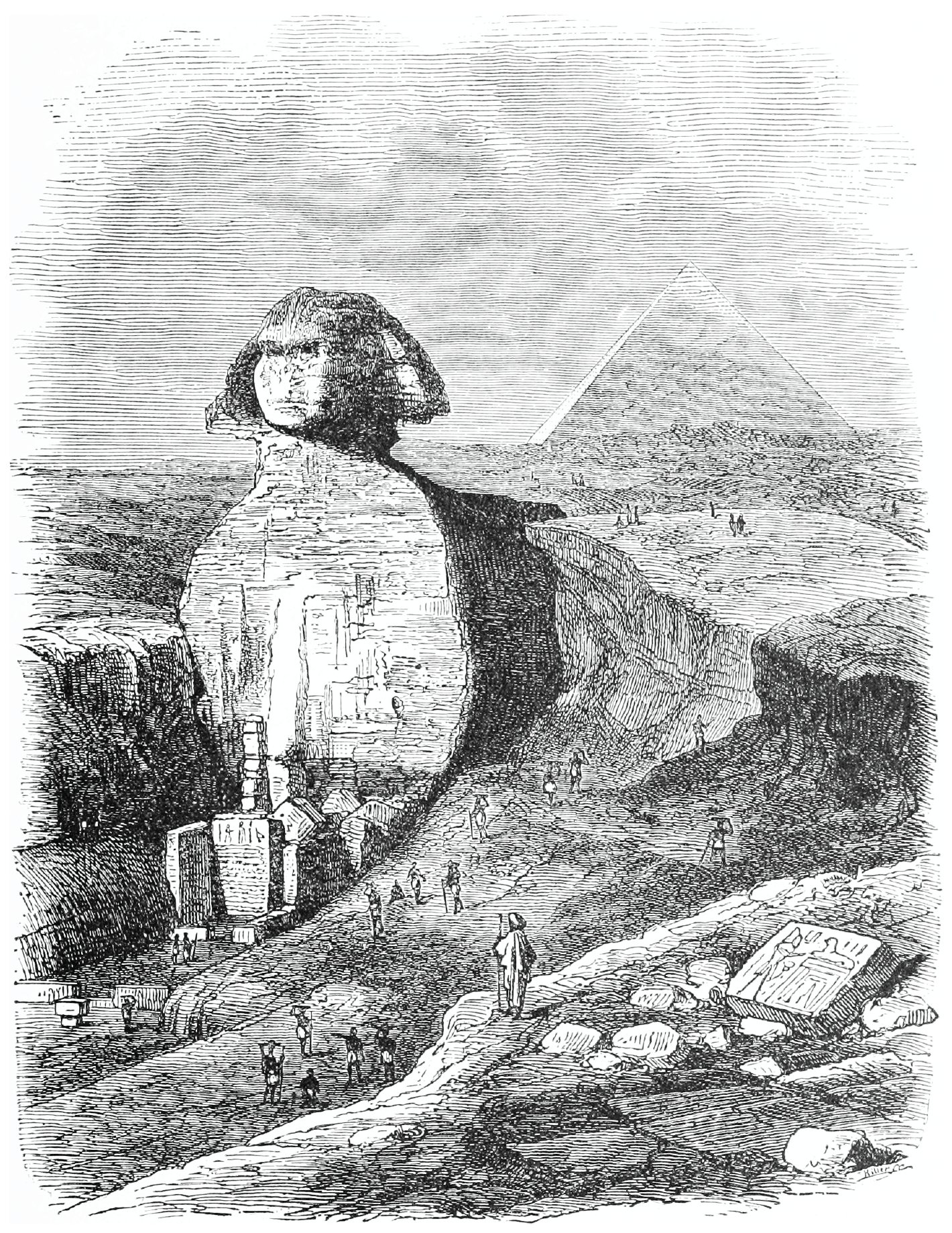

The beginnings of this noble process, however, go back way farther than that. The ancient denizens of Mesopotamia, China, Egypt and the Roman Empire preserved fruits in a similar way using honey, long before Christianity. Each appears to have discovered the method independently, and since it was a very long time ago we cannot say for sure who did it first.

Initially, the main problem was how long food would last. In a hot climate, fruit may start to decay very quickly, so that storing and transporting it, especially to faraway places, was difficult. Preserving it with honey was found to be a practical solution to all of these problems. Honey consists mostly of simple sugars, allowing us to eat any fruit preserved in it without worries, months or even years later, and without any need to store them at low temperatures. Apart from the fruit lasting longer, in ancient times they could enjoy the amazing flavor properties of such fruit.

The history of candied fruit is inseparably associated with the history of sugar itself, as well as the products it is used in. The earliest sugar cane plantation we know about was found in Papua New Guinea, dating from 8000-4000 BC. Sugar cane, after sugar beet, has the highest natural plant sugar content. It took a while before we learned to isolate the sugar from it in its pure form, however. At first, the cane was simply chewed, not unlike as we do candies or gum today, since this released its sweet flavor. It was also used in syrups and preparations.

Although originating from Papua, it moved across Asia, including China and India. It was in India where sugar refining was developed, sometime between 500 BC and 500 AD. From there, the plantation and associated technology spread to Persia and, beginning with the Arabic conquest of 637 AD, it continued all across the Arab world of the time, reaching the Mediterranean. Sugar cane growing in Egypt, Persia, Cyprus, Sicily, Southern Spain and Northern Africa became serious business by about 1000 AD. There is no certainty as to who was the first to use sugar for fruit preservation and, by extension, candying, but it is highly probable that it was the Arabs.

The Egypt of circa 1000 AD became a very important producer and consumer of sugar. This included the custom of decorating tables with large-sized sugar sculptures of trees, buildings and animals, later adopted in Medieval Europe. The Egyptians also had a tradition of giving away sweets and sugar to the poor, who were allowed to take the figures away after a party. One such figure could weigh as much as one ton. During exceptionally lavish banquets, the guests would consume and give away as much as 60 to 70 tons of sugar!

Back then, sugar was used both for hard and soft products, with the former chiefly being candied fruits. They could be stored for long periods, making them perfect for Medieval trade as they survived long sea and land journeys well. Soft products, such as baklava, would spoil too quickly, and only appeared in Europe with the Ottoman conquests, then later with immigrants in the 20th century. Pure sugar was traded as well, or, it should be said, principally. It also formed one of the basic ingredients of medications, with hard candy and sugar pills becoming the ancestors to most modern sweets, save for those based on chocolate and toffee.

The import of sugar into Europe began in about 1000 AD, although at the time sugar was still treated as a spice. At first it was merely a novelty product, one not previously known. The Venetians controlled a significant part of the trade with Arabic countries, Europe and Constantinople, and were the first to appreciate sugar. Officially, the state fought against Islam, but in practice it would find itself skirmishing against Pisa and Genoa more frequently, collaborating with those that could bring profit. We know that Venice had been trading in sugar since 966 from records that survive from one of the warehouses. From there, sugar could be exported to Central Europe, to the Slavic countries and the Black Sea.

It was, however, the Crusades that prevented Venice from seizing control of this new spice market (the old spices being mostly pepper and saffron, known and imported much earlier). Venice supplied and not uncommonly financed the Crusaders, in turn gaining access to ports and earning various privileges. During their quests, the Crusaders stumbled upon plantations of hitherto-unknown sugar cane, and passed the news to the Venetians. Until then, the Venetians had only imported sugar on a very small scale, it was still not widely known and nobody knew how to produce it.

Apart from controlling a large chunk of the Mediterranean trade, the Venetians supervised certain ports (such as the docks of Constantinople). They were on good terms with various Arabic ports (such as Alexandria), which, at the time, were much larger trade centers than their European counterparts. They also possessed significant financial assets, which permitted them to sponsor the Crusades. Known for their penchant for business, the Venetians took an interest in sugar, sensing its potential for commerce. They bought it in many places, from Spain and Morocco, through Tunisia and Sicily, Damascus and Antioch, all the way to Constantinople. They would sell it back home and export it to the North, especially the German states and France. The longer the distance it was traded, the more expensive it became. The price of sugar could be enormous, with one kilogram sometimes costing the equivalent of two months' work of a general laborer!

In the 13th century, the regular import began of sugar and sugar products into Europe. After about the year 1300, the price of sugar started to fall from its earlier astronomically high prices. As it became cheaper, it became more affordable not only for the richest people in the country, but also the gentry and even well-to-do townsfolk.

The first patisserie was founded in Venice as early as 1150. After that, European craftsmen developed the sugar-making technology, and by the beginning of the 13th century, several locations in Italy managed to develop large-scale candy production. The earliest products sold were mainly candied or sugar-preserved fruits, and hence the idea that confectionery was invented in Italy. This stereotype lasted in Europe until the 19th century, and Italy remains heavily associated with the sugar sector even today.

The Italians viewed sugar processing as very important. As a testament to its dominant role, back in 1343 even Pope Clement VI conferred the Bishop of Apt the title of “Master of Confectionery”. This distinction made the town a privileged location for the production of candied fruits.

The candied fruits imported from the Arab countries at the time were mostly citrus fruits: oranges, lemons, limes and tamarinds. In the beginnings of the profession in Europe, patisseurs typically candied the same fruits, knowing the recipes to be tried and true. However, they soon realized that the same could be done with local products as well, and began including their fruits and flowers. Such sweets were ideal for consumption during winter, when storing fresh fruits was not possible. If one could not afford these products, the choice was usually dried fruits or other, similar products: raisins, dates or figs. The first fruits to be candied after citrus fruits were probably plums and apricots. Often the stone would be left in, so that the fruit maintained its original shape. Sugar was also used to preserve many other fruits, vegetables, herbs, roots and plant stalks known for their medical properties.

1470 saw the opening of the first Venetian refinery. As imported sugar was not well-purified and was of low quality, it was used as a semi-product and refined further to produce white, pure, high quality, crystalline sugar. More countries started establishing their own trade contacts and importing sugar, but Venice would remain in control of this sector of the food industry for a long time, partly thanks to such actions as marrying into the Cypriot dynasty, when Cyprus was a large sugar producer.

In 1453, the Turks conquered Constantinople, shutting down all of the caravan trade routes between the Middle East and Europe. In a short time, spice prices skyrocketed, with the outlook for sugar being bleak. While Europeans did take over many Mediterranean plantations, such as those in Cyprus, Crete and Sicily, they were past their prime and no longer efficient. Sugar was to become very expensive once again.

The plantations in India were the largest and most prosperous, and it became clear that the discovery of a maritime route to India could bring great profits. In 1497, Vasco da Gamma sailed around Africa and established an alternate, direct route, if a rather risky one. His feat was the cause of the slow decline of the Italian republics and the blooming of Portugal.

This new route to India, while solving many problems, was still a daunting journey of many thousands of kilometers. Growing sugar cane and producing sugar without such a journey would be the ideal solution, and was favored by the geopolitical situation of the time: the fall of Constantinople coincided with the discovery of the Americas.

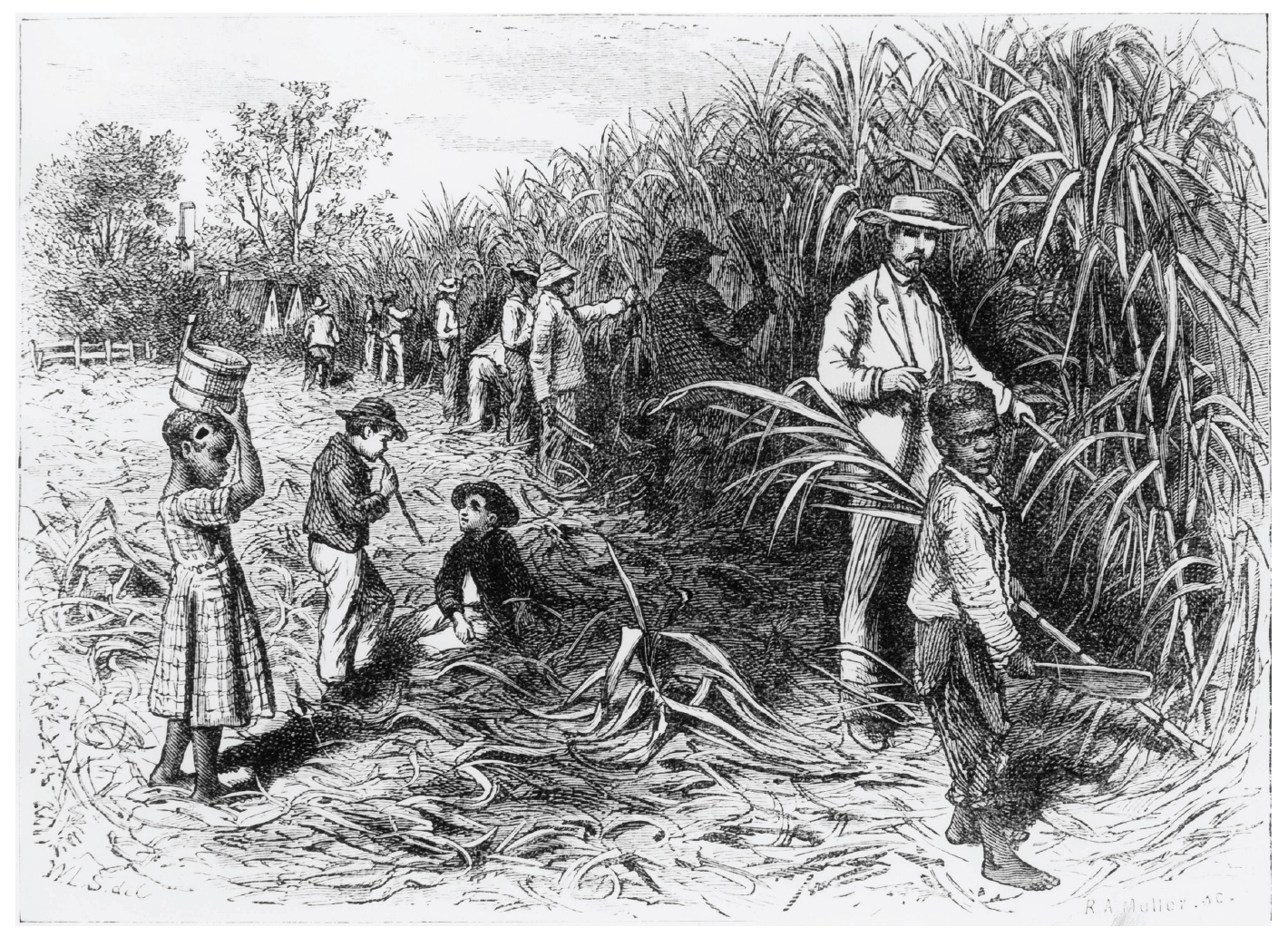

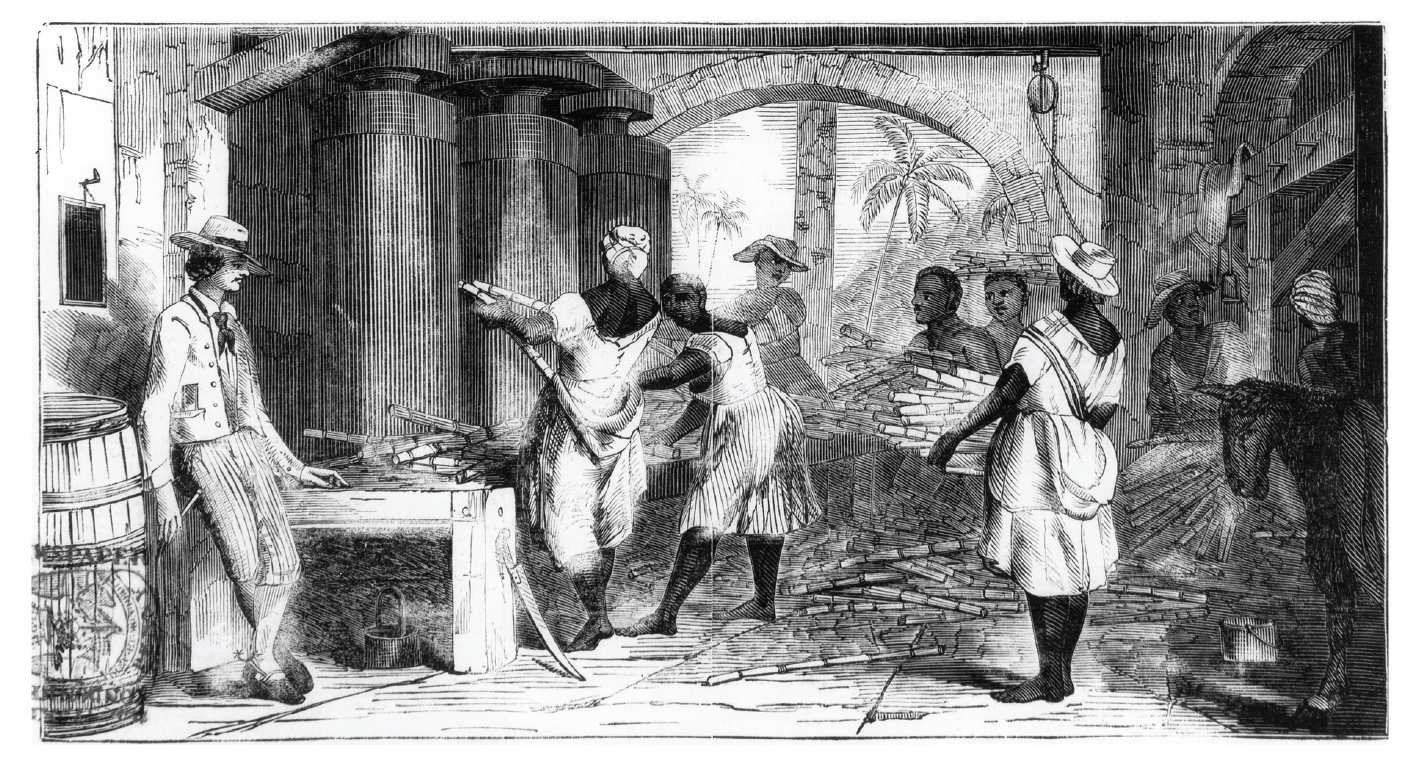

The Portuguese quickly became leaders in growing sugar cane on islands off Africa, initially Madeira, and then later on in Brazil. The Spaniards followed suit, creating plantations in the Canaries. During his second expedition in 1493, Christopher Columbus personally supervised the founding of a sugar plantation on Hispaniola (present-day San Domingo). Other Spanish plantations were situated in Mexico, Cuba, Jamaica and Puerto Rico.

Establishing sugar cane escalated very quickly, and the plantations grew ever-stronger. Antwerp and Amsterdam, both Atlantic ports importing sugar from the Americas, became important centers and founded their own refineries. The prices dropped, making sugar imports from the Middle East, the Mediterranean and India virtually non-existent. For the next 100 years, Spain and Portugal would hold the monopoly on sugar production.

Owing to the fact that the prices remained constant, sugar became affordable for the middle classes. While it still remained a luxury good, more people could afford at least small amounts of it. In the 17th century, having grown resentful of the Hispano-Portuguese monopoly, England, France and the Netherlands attacked and conquered various parts of South America, founding their own plantations. Over time, their profitability rose. The trade model that would become dominant in the 18th century began emerging as well: European goods were sold to Africa, African slaves were sold to the New World, and sugar, tobacco, coffee and cotton then sold to Europe.

At about the same time as candying was growing, the techniques of creating hard candy, a cheaper alternative to “real” candied fruits, started to develop. The earliest mentions come from books on medicine and nutrition, since initially sugar was treated as a medication. Part of this approach remains even today in the form of medications, such as throat lozenges. One of the first descriptions of candied fruits is the "Libre de totes maneres de confits" ("Book on various ways of making sweets"), an anonymous collection of cooking recipes published in Catalonia around the end of the 14th century. It contains 33 recipes for various desserts based on honey and sugar, with candied fruits (25 recipes), marmalades, compotes and nougats. Among the ingredients used one can find: watermelons, almonds, lemons, quince, turnips, parsnips, carrots, peaches, apples, pears, walnuts and cherries. Then there’s Thomas Elyot’s "Castel of Helth", published in 1541, describing candied ginger as a remedy for an excess of phlegm. Even earlier, candying is mentioned in the anonymous "Treasure of Pore Men", published in 1526.

In the 16th century, European gastronomy became dominated by the de’ Medici family, who introduced an element of finesse to renaissance courts. Catherine de’ Medici hired the famous Nostradamus as her personal cook. He authored one of the finest French texts on making sweets: “Treatise on Cosmetics and Jams”. The book contained advice regarding the maintenance of one’s beauty, as well as candied fruit recipes. Nostradamus divulged his ways of candying entire lemons and oranges, as well as quince and pear quarters.

The banquets that took place at the most opulent of European courts were documented by Renaissance chefs in their books. Cristoforo di Messisbugo in "Banchetti, composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale" from 1549, as well as Bartolomeo Scappi in "Opera dell'arte del cucinare" from 1570. The authors wrote that, at the end of the courses, the dishes would be taken away, and, in a separate room, wine and “spices” would be served. They were either, in fact, spices or honey- or sugar-candied fruits. The guests would then eat ginger, coriander and anise, as well as candied melons, lemons, oranges, pomegranates and chestnuts, along with sugar-coated nuts. They would be used to make more advanced products that preceded modern nougats. Candied fruits were treated not just as a treat; they were supposed to “close” the stomach and facilitate digestion.

Owing to the existence of ever more cookbooks, the art of candying and other confectioning techniques reached the gentry. Confectionery became a fashionable pastime for housewives, and by the middle of the 18th century, it became a desirable, if not indispensable, ability for a young wife to possess.

The prices of sugar slowly but steadily dropped. Formerly exclusive, it was no longer inaccessible for the poor, and became less attractive to the rich. This situation caused the emergence of the non-sweetening fad (in France first), which, in turn, led to the emergence of the dessert as a separate dish. Even though the prices of sugar were steadily dropping, sweets remained expensive. This was because confectionery was treated almost on par with alchemy, arcane to all but a few. The recipes remained shrouded in mystery, with the ingredients and their proportions remaining a jealously-guarded secret. Another reason behind the high prices of cakes and pastries was the long time it took to prepare them. It now made more sense to buy a sweet instead of preparing a homemade one.

In 1747 a Prussian chemist, Andreas Marggraf, demonstrated how to extract sugar from a sugar beet for the first time. He mixed brandy with the beet and obtained sugar crystals. This marked the beginning of sugar beet cultivation in Prussia. Six decades later, Napoleon called on French industrialists to build a cultivation industry to start making sugar from beets, following the Prussian example. This is what happened, and the first half of the 20th century saw the world’s sugar production grew sevenfold. No other basic crop saw such a leap, and as a consequence the prices dropped so much that sugar became an everyday product.

The development of the techniques and industry led to the mechanization and acceleration of the candying process. With the use of vacuum pumps, the processing time dropped from 2 weeks down to 12 hours. It still remains a process requiring much work and resources, and candied fruits are still an expensive product. Since 1985 Kandy has continued this centuries-old candying tradition. We make products without the use of preservatives, artificial additives or GMOs - the only ingredients we need are fruit and sugar. Currently, Kandy remains one of the leading candying companies in Poland and Europe.

Tim Richardson „Sweets. A History of Candy”

Beth Kimmerle “Candy: The Sweet History”

Beth Kimmerle “Chocolate: The Sweet History”

Paul Bairoch „Economics And World History”

https://gastronomyarchaeology.wordpress.com/2011/11/25/candied-fruits-part-1/

http://www.candyhistory.net/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candied_fruit

http://www.foodreference.com/html/fcandiedfruit.html

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/92425/candied-fruit

http://www.ifood.tv/network/candied_fruit

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/10/081030-oldest-candy-facts-halloween_2.html

http://www.confi-fruit.com/history.html

http://www.oldcook.com/en/medieval-fruit

http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-candied-fruit.htm

Author: Dariusz Socik

Editing and proofreading: Ewa Socik

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

All rights reserved.

All contents published on this website are under legal protection of the regulation stated in Copyright and Related Rights Act of 4th of February 1994 (consolidated text published in Journal of Acts of 2018, item 1191). Without author’s permission it is forbidden to replicate, copy, reprint, keep or recycle them, using electronic devices or means, both in whole or in part. It is also forbidden to further diffuse or disseminate contents due to the Article 25 (1) Point (1) Letter (b) of Copyright and Related Rights Act of 4th of February 1994.